I couldn’t agree more with the points made by identity architect James Brown in a very disturbing piece he has posted at The Other James Brown.

James explains how the omnipresent Facebook ![]() widget works as a tracking mechanism: if you are a Facebook subscriber, then whenever you open a page showing the

widget works as a tracking mechanism: if you are a Facebook subscriber, then whenever you open a page showing the ![]() widget, your visit is reported to Facebook.

widget, your visit is reported to Facebook.

You don’t have to do anything whatsoever – or click the widget – to trigger this report. It is automatic. Nor are we talking here about anonymized information or simple IP address collection. The report contains your Facebook identity information as well as the URL of the page you are looking at.

If you are familiar with the way advertising beacons operate, your first reaction might be to roll your eyes and yawn. After all, tracking beacons are all over the place and we’ve known about them for years.

But until recently, government web sites – or private web sites treating sensitive information of any kind – wouldn’t be caught dead using tracking beacons.

What has changed? Governments want to piggyback on the reach of social networks, and show they embrace technology evolution. But do they have procedures in place that ensure that the mechanisms they adopt are actually safe? Probably not, if the growing use of the Facebook ‘Like’ button on these sites demonstrates. I doubt those who inserted the widgets have any idea about how the underlying technology works – or the time or background to evaluate it in depth. The result is a really serious privacy violation.

Governments need to be cautious about embracing tracking technology that betrays the trust citizens put in them. James gives us a good explanation of the problem with Facebook widgets. But other equally disturbing threats exist. For example, should governments be developing iPhone applications when to use them, citizens must agree that Apple has the right to reveal their phone’s identifier and location to anyone for any purpose?

In my view, data protection authorities are going to have to look hard at emerging technologies and develop guidelines on whether government departments can embrace technologies that endanger the privacy of citizens.

Let’s turn now to the details of James’ explanation. He writes:

I am all for Gov2.0. I think that it can genuinely make a difference and help bring public sector organisations and people closer together and give them new ways of working. However, with it comes responsibility, the public sector needs to understand what it is signing its users up for.

In my post Insurers use social networking sites to identify risky clients last week I mentioned that NHS Choices was using a Facebook ‘Like’ button on its pages and this potentially allows Facebook to track what its users were doing on the site. I have been reading a couple of posts on ‘Mischa’s ramblings on the interweb’ who unearthed this issue here and here and digging into this a bit further to see for myself, and to be honest I really did not realise how invasive these social widgets can be.

Many services that government and public sector organisations offer are sensitive and personal. When browsing through public sector web portals I do not expect that other organisations are going to be able to track my visit – especially organisations such as Facebook which I use to interact with friends, family and colleagues.

This issue has now been raised by Tom Watson MP, and the response from the Department of Health on this issue of Facebook is:

“Facebook capturing data from sites like NHS Choices is a result of Facebook’s own system. When users sign up to Facebook they agree Facebook can gather information on their web use. NHS Choices privacy policy, which is on the homepage of the site, makes this clear.”

“We advise that people log out of Facebook properly, not just close the window, to ensure no inadvertent data transfer.”

I think this response is wrong on a number of different levels. Firstly at a personal level, when I browse the UK National Health Service web portal to read about health conditions I do not expect them to allow other companies to track that visit; I don’t really care what anybody’s privacy policy states, I don’t expect the NHS to allow Facebook to track my browsing habits on the NHS web site.

Secondly, I would suggest that the statement “Facebook capturing data from sites like NHS Choices is a result of Facebook’s own system” is wrong. Facebook being able to capture data from sites like NHS Choices is a result of NHS Choices adding Facebook’s functionality to their site.

Finally, I don’t believe that the “We advise that people log out of Facebook properly, not just close the window, to ensure no inadvertent data transfer.” is technically correct.

(Sorry to non-technical users but it is about to a bit techy…)

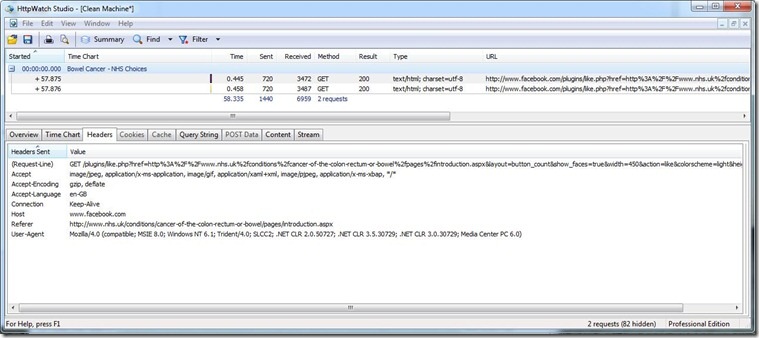

I created a clean Virtual Machine and installed HTTPWatch so I could see the traffic in my browser when I load an NHS Choices page. This machine has never been to Facebook, and definitely never logged into it. When I visit the NHS Choices page on bowel cancer the following call is made to Facebook:

So Facebook knows someone has gone to the above page, but does not know who.

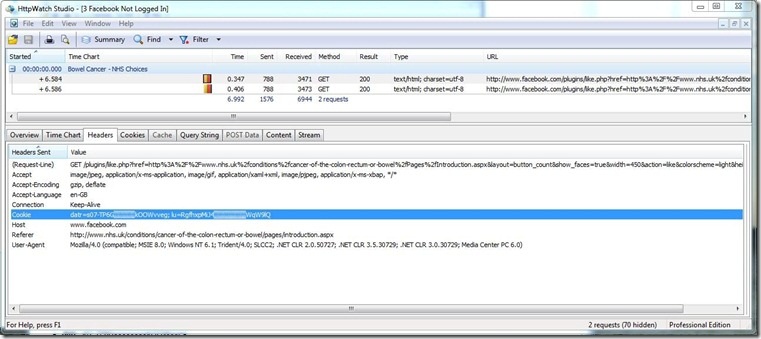

Now go Facebook and log-in without ticking the ‘Keep logged in’ checkbox and the following cookie is deposited on my machine with the following 2 fields in it: (added xxxxxxxx to mask the my unique id)

- datr: s07-TP6GxxxxxxxxkOOWvveg

- lu: RgfhxpMiJ4xxxxxxxxWqW9lQ

If I now close my browser and go back to Facebook, it does not log me in – but it knows who I am as my email address is pre-filled.

Now head over back to http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/cancer-of-the-colon-rectum-or-bowel/pages/introduction.aspx and when the Facebook page is contacted the cookie is sent to them with the data:

- datr: s07-TP6GxxxxxxxxkOOWvveg

- lu: RgfhxpMiJ4xxxxxxxxWqW9lQ

So even if I am not logged into Facebook, and even if I do not click on the ‘Like’ button, the NHS Choices site is allowing Facebook to track me.

Sorry, I don’t think that is acceptable.

[Update: I originally misread James’ posting as saying the “keep me logged in” checkbox on the Facebook login page was a factor in enabling tracking – in other words that Facebook only used permanent cookies after you ticked that box. Unfortunately this is not the case. I’ve updated my comments in light of this information.

If you have authenticated to Facebook even once, the tracking widget will continue to collect information about you as you surf the web unless you manually delete your Facebook cookies from the browser. This design is about as invasive of your privacy as you can possibly get…]