Bruce Schneier in Beyond Fear coined a phrase:

one of the goals of a security countermeasure is to provide people with a feeling of security in addition to the reality. But some countermeasures provide the feeling of security instead of the reality. These are nothing more than security theater. They’re palliative at best.

The Common Names debâcle at Google Plus is a variant of this, where the supposed protections are manifestly not working. Google’s stated policy on this is that you should use your ‘common name’ – normatively defined to have exactly two words in it, in a naïve English speaking way, that fails in a huge number of common English cases, let alone other languages.

he is trying to make sure a positive tone gets set here. Like when a restaurant doesn’t allow people who aren’t wearing shirts to enter.

so it is explicitly designed to exclude ‘people not like us’ from the space.

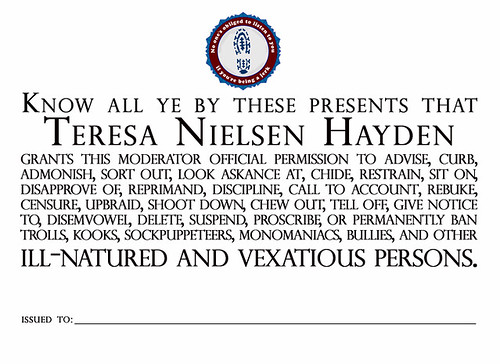

Early users can set the tone for a network, but one that has aspirations to include most people will need to support multiple different communities within it. If you want a positive tone, you have to work at it, and empower the tummlers to maintain it. Teresa Nielsen-Hayden put it well:

1. There can be no ongoing discourse without some degree of moderation, if only to kill off the hardcore trolls. It takes rather more moderation than that to create a complex, nuanced, civil discourse. If you want that to happen, you have to give of yourself. Providing the space but not tending the conversation is like expecting that your front yard will automatically turn itself into a garden.

2. Once you have a well-established online conversation space, with enough regulars to explain the local mores to newcomers, they’ll do a lot of the policing themselves.

More from Teresa and from John Scalzi.

The initial flavour of Google Plus, because it was seeded by Googlers and other geeky folk they invited, was like pre-Eternal September Usenet – it had a cultural coherence because we were all geeks. As it grew to 25 million users, this could not hold.

Blogs deal with this by making it clear who the site owners are, and empowering them to manage commenters. Twitter does it by not showing you comments unless you chose to see the commenter, or if they address you directly. Google Plus is an uneasy hybrid of the two.

You can delete and block commenters on your postings, like a blog, and if you reshare someone’s post, it starts a new comment thread, like a blog. However, anyone can @ or + your name and drag you into another comment thread via notification, and then you get notified of other follow-ups too, making griefing and harassment all too easy.

Enforcing ‘common names’ does nothing to help this; it just means your trolls and griefers will be using plausibly American-looking names that may or may not be their own, while those with unusual names, will either be excluded outright or easily preyed on by the griefers reporting them, which is what I suspect happened to Violet Blue tonight.

Once you are suspended, the verification process is crude and manual, and also easily gamed. Kellan warned about this problem:

If you’ve never run a social software site … let me tell you: these kinds of false positives are expensive.

They’re really expensive. They burn your most precious resources when running a startup: good will, and time. Your support staff has to address the issues (while people are yelling at them), your engineers are in the database mucking about with columns, until they finally break down about build an unbanning tool which inevitably doesn’t scale to really massive attacks, or new interesting attack vectors, which means you’re either back monkeying with the live databases or you’ve now got a team of engineers dedicated just to building tools to remediate false positives. And now you’re burning engineer cycles, engineering motivation (cleaning up mistakes sucks), staff satisfaction AND community good will. That’s the definition of expensive.

And this is all a TON of work.

And while this is all going down you’ve got another part of your company dedicated to making creating new accounts AS EASY AS HUMANLY POSSIBLE. Which means when you do find and nuke a real spammer, they’re back in minutes. So now you’re waging asymmetric warfare AGAINST YOURSELF.

This is the hole Google is now in. A surprisingly large number of people I know, who’ve been discussing civilly online for years, have fallen foul of Vic’s Procrustean name rules. When they point this out, they’re harrassed by ‘Real named’ dickheads telling them to shut up and change their name, both in public and by being +-summoned by the trolls, and they have to find Google plus’s well-hidden blocking tools rather quickly. Or give up and go elsewhere.

Now, Google has announced that they are verifying some people’s names, to prevent impersonation. Trouble is, they haven’t said how . Twitter verifies celebrities via an opaque process. Amazon does it by checking your name matches a Credit Card. Google Search uses rel=”me” and rel=”author” microformats. What Plus does is unknown. One of my profiles is verified, possibly because I went through the verification process on Google Knol before.

This is also Identity theatre – Google saying ‘trust us’, rather than revealing the rel=”me” link from the person’s page that we already know.

Vic Gundotra needs to stop digging this hole. Scrap the normative ‘common names’ policy, add a coherent name verification and linked-site verification so we can tell the people we already know, and make moderation tools visible and available so we can curate the conversations ourselves.

With this, and an apology to those already ensnared by the existing process, he could maybe prevent Plus from being spoken of only alongside Wave and Knol.

- my.nameis.me has testimonials on the nuances of names

- jwz is shocked by othering of the anonymous

- The EFF’s case for pseudonyms

- Journalists tempted by slumming